The Public Cresta Encyclopaedia Online

DEAR CRESTA AND SKELETON RIDERS

We are SVEN-HOLGER, a boutique outdoor lifestyle design brand. The theme of our Winter Collection is the skeleton sport. For fashion research purposes we purchased many rare skeleton sport articles published in previous centuries in magazines and books. While researching fashion styles of this sport, we were fascinated by the crucial role the Cresta Run played in the development of this sport. Therefore, by preserving the original articles from Cresta Run, we have made them available for future generations of riders and enthusiasts. Securing the fact that these stories, race results and historic events will not disappear. Incidentally, many of these are the last remaining artifacts from 1889-1940 and were acquired by us primarily at an auction. The articles acquired by SVEN-HOLGER have been donated to the SMTC archive and its President James Sunley in 2019.

We have digitized these and have included them in our Skeleton Sport Encyclopedia. Any additional relevant historical facts and stories you may wish to send us will be gratefully received. We would appreciate you informing us in case of possible copyright infringement. As well, if any of the text or images causes offence or upset, please do not hesitate to contact us.

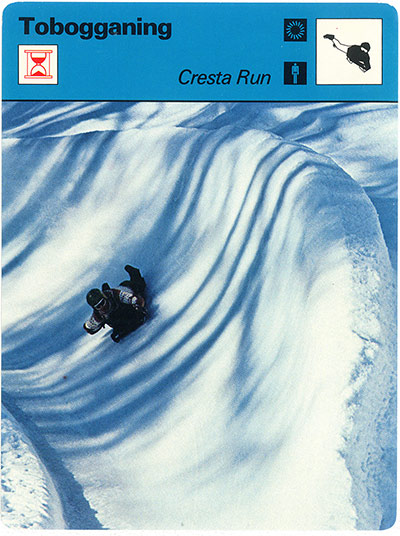

‘The skeleton originated in St. Moritz, Switzerland, as a spinoff of the popular British sport called Cresta sledding. Although skeleton ‘sliders’ use equipment similar to that of Cresta ‘riders’, the two sports are different: while skeleton is run on the same track used by bobsleds and luge, Cresta is run on Cresta-specific sledding tracks only. Skeleton sleds are steered using torque provided by the head and shoulders. The Cresta toboggan does not have a steering or braking mechanism, though Cresta riders use rakes on their boots in addition to shifting body weight to help steer and brake.’

Source: Wikipedia

The Cresta Run - an introduction

Several excellent and detailed books have been written on the Cresta Run, in the last 40 years. For example 'The Cresta Run' by Michael Seth-Smith in 1975 and 'Apparently Unharmed - Riders of the Cresta Run' by Michael DiGiacomo in 2000. There has also been a centenary booklet and a beautiful hard-backed photography book. Indeed two books were written about the Cresta Run in 1894 'Tobogganing on Crooked Runs' by Hon. Harry Gibson, and 'Notes on Tobogganing' by Theodore Cook. There are also a number of films which date back to the 1920's and are added to regularly on You Tube. Yet surprisingly few people seem to have heard of the Cresta Run. Often referred to as a woman she is indeed 'mysterious'.

-

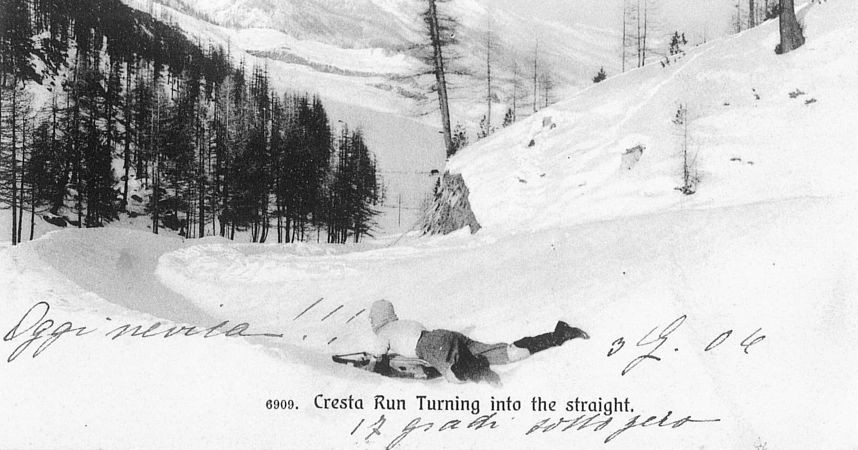

1/3Postcard bought on eBay stamped from 01.06.1906, Cresta Run Turning into the straight.

-

2/3Cresta Run turning into the straight.

-

3/3Tobogganing on the Cresta Run, St. Moritz: Old c. 1950 (est.)

BBC Commentator and reporter for the 1947-8 Winter Games describes it like this:

"Streamlined is an overworked word, but it describes perfectly the beautifully chiselled contours

of the Cresta Run, which snakes down the mountain for exactly three-quarters of a mile, its five

foot wide track of wicked ice glittering unsheathed in the sun like purest steel, and like finely

forged steel the Cresta bends and twists into a myriad pitfalls for the human ball of quick-silver

as it hurtles its way down the intricate puzzle, a false move, an unsteady hand, and error of eye

or timing and the ball is over the edge.”

Anatomy of the cresta run

- Overall distance (Top to finish) 1212m (3977ft)

- Overall drop (Top to Finish) 157m (514ft)

- Overall gradient (Top to Finish) 1:8.7 to 1:2.8 (avg 1:7.7)

- Distance from Junction 890m (2921ft)

- Drop from Junction 101m (332ft)

- Gradient from Junction avg. 1:8.8

The Cresta Run follows the natural contour of the landscape between St. Moritz and the former hamlet of Cresta, which is part of today’s town of Celerina. It is built every year anew from snow (today, artificial snow is used) - currently by an Italian builder named Natalino Bera and his crew - using only shovels, brushes and a metal form to define the shape of the icy run, which has barely changed since 1885. The original plans were devised by a 22-year old geometrician and implemented under the guidance of Major Bulpett. The first committee, with boots and arms linked, trudged up and down the marked line in the snow, until it was trampled down and hardened by the frost. The first run took over two months to build and was completed in 1885.

Nowadays the Run is still created in a similar way. The design has changed slightly in that it is perhaps more refined and safer as riders have become faster. Building starts at the end of November with snow being moulded using shovels and brushes and is all done by eye; the expertise having been passed down through the generations.

There are two parts to the season - the run opens in the second half of December from Junction and later from Top. Today, up to 800 riders ride 13,000 courses in a season.

Entry points

The Cresta Run has two entry points: Top (at the very top of the track) and Junction. All beginners must start from Junction, which lies about one-third of the way down from Top. Everyone who wants to start from Top, has to prove his skills in riding from Junction before the secretary allows his first Top ride. This means recording times of 48 seconds from Junction. He also needs a mentor – an experienced rider – to introduce him to Top riding with careful advice. First time riders from Top are often told "Congratulations, you are now a Cresta Rider."

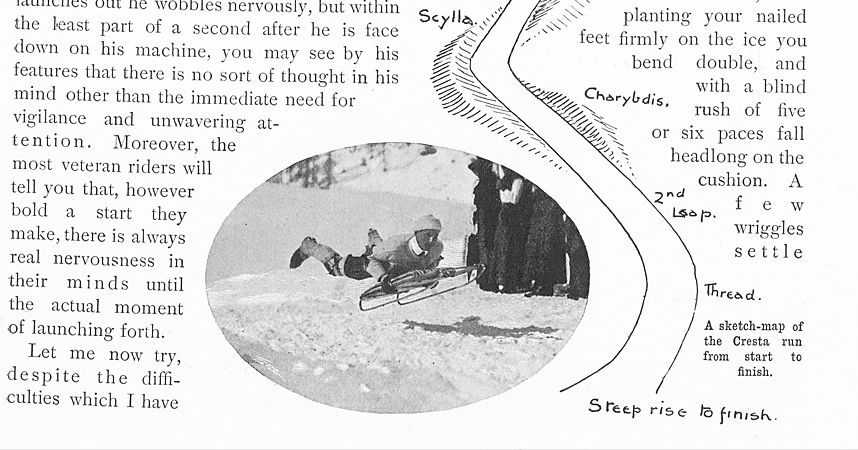

Turns

The Cresta Run consists of 10 unique turns, some of which are quite a challenge; they are not as super-elevated as opposed to bobsled runs. The most famous one is Shuttlecock, which acts as a safety valve, throwing out anyone who has lost control at that point into a well-prepared bed of hay and loose snow. The Cresta has shallow banks which means a rider has to 'ride' it, unlike luge or bobsled runs, where you can get to the end safely, come what may.

Many of the names on the Run are named after Cresta pioneers: Church Leap, Curzon, Brabazon, Thoma, Junction Hut, Rise, Stream Corner, Bledisloe Straight - named after the Bledisloe family, two members of whom were SMTC presidents - Battledore, Shuttlecock - Shuttlecock is the trickiest turn of all and therefore the most famous one as well, as it has caused thousands of falls in its 130 years of existence. If someone falls at Shuttlecock, the secretary at the tower rings a bell, making anyone in sight halt and look for the fallen rider, waiting for him to stand up and wave his arms, indicating he’s alive. Then, the tannoy declares "(rider name) is up and apparently unharmed." The next rider is then allowed to start, as soon as the track is clear. Lt. Colonel Digby J. Willoughby said he’d flown out at shuttlecock more than 50 times, the record for a club member, and one in fourteen rides ends here - Stream Corner, Bulpetts, Scylla Charybdis, Cresta Leap and Finish.

Races, Timekeeping and records

Over 40 different competitions take place on the Cresta each year. They are differentiated according to the following criteria: Handicap or open race and Start from Top or Junction.

In a handicap race, each competitor is assigned a handicap by the committee based on his previous results. This makes it possible even for less experienced or older riders to compete with the champions. In an open race, the ranking is determined by the actual recorded times. Some races start from Top, whereas some start from Junction, one-third down the run.

Next time, I think I’ll try it faster Richard A. Wolters

Top is more difficult and dangerous and therefore only open to experienced riders. There is a special time called Flying Junction, where riders start from Top but their time is measured between Junction and Finish. The four main challenges each year are the Grand National, the Brabazon Cup, the Curzon Cup and the Morgan Cup. Only a few men have won all four main races in a single season, also called the Grand Slam. During races national flags fly from the Tower's flagpole, for example, the union flag for the British military services race or the American flag for the Morgan Cup.

Awards Show

Prize-giving for each race is normally held on the terrace at the Kulm Hotel overlooking the frozen lake. Riders who finish third and second receive a bottle of Champagne and a small trophy. The winner receives a trophy, a replica trophy, and a bottle of Champagne. The trophy cup is filled with champagne, paid for by the winner, which is passed round, and finally an official photograph is taken. In the Gunter Sachs Challenge Cup, the first six finishers receive gold buttons.

The Cresta Colours

The first eight finishers in the Curzon, Grand National, Brabazon and Morgan races win the 'Cresta Colours', and are termed 'Colours Riders'. They are entitled to wear a maroon and gold tie - the colours of the St Moritz Tobogganing Club. Below is a table of all historic and current races:

| Name | Type | Type | First held in |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astor Cup | |||

| Bacon Speed Cup | Top | ||

| Hans Badrutt Trophy Championship Cup | Open | Flying Junction | 1960 |

| Johannes Badrutt Memorial Trophy | Handicap | Top | 1962 |

| Barclay-Harvey Speed Cup | |||

| Bartley Bear Race Open | Open | Junction | 1964 |

| Bathurst Speed Cup | |||

| Nino Bibbia Challenge Cup | Open | Junction | 1968 |

| Archie Birkin Cup | |||

| Bledisloe Cup | Junction | 1982 | |

| Julian Board Seniors Cup | Handicap | Junction | 1950 |

| Bott Handicap Cup | Handicap | Top | 1905 |

| Brabazon Trophy | Open | Top | 1966 |

| Brothers Race | |||

| Carlton Challenge Cup | |||

| Cartier Challenge Trophy | Open | Top | |

| Claude Cartier Challenge Cup | Open | Junction | 1955 |

| Beatrice Cartwright Cup | |||

| The Member's Children's Race (Boys 14-17) | Open | Stream | 1985 |

| Commonwealth Winter Games | |||

| Coppa d’Italia | Handicap | Top | 1929 |

| Coronation Cup | |||

| Coupe de France | |||

| Crawford Cup Handicap | Handicap | Top | 2010 |

| Cresta Race for Employees | |||

| Curzon Cup 'Cresta Derby' (formerly Ashbourne Cup) | Open | Junction | 1910 |

| East vs West Race | |||

| Escalante Cup | Handicap | Junction | 1957 |

| Fathers-and-Sons Race Open | Open | Junction | 2004 |

| Fleetwood Wilson Cup | |||

| Freshman’s Cup | Top | ||

| Fryer Cup | Stream | ||

| Roger Gibbs Challenge Cup Handicap | Handicap | Junction | 1994 |

| Gibson Cup | Top | ||

| Grand National | Open | Top | 1985 |

| Calish Grischun | Handicap | Top | 1930 |

| Harland Trophy | Handicap | Top | 1956 |

| Heaton Gold Cup | Open | Junction | 1931 |

| International Race | Handicap | Top | 2015 |

| Junction Night | Open | Junction | 1994 |

| Junior Cup (Kids 8-15) | Open | Stream | |

| Knapp Cup (formerly Cresta Cup) | Open | Top | 1934 |

| Ladies’ Race Open | Open | Junction | 1987 |

| Fairchilds MacCarthy Cup | Team Handicap | Junction | 1956 |

| Macklin Cup | |||

| Marsden Speed Cup | Handicap | Top | 1969 |

| Nigel Moores Memorial | Open | Junction | 1978 |

| Morgan Cup | Open | Top | 1935 |

| Mug’s Mug | |||

| Novices Cup | |||

| Baron Oerzen Cup | Handicap | Junction | 1930 |

| Payne Cup | Open | Top | 2007 |

| San Pellegrino Cup | |||

| Georges Prade Cup | |||

| Prince Philip Inter Services | Team Open | Top | 1954 |

| President's Race | Handicap | Junction | |

| Pulitzer Texan Long Horn Trophy | |||

| Lady Ribblesdale Cup | |||

| Gunter Sachs Challenge Cup 'The Buttons' | Open | Top | 1964 |

| The Services' Silver Spoon | Handicap | Junction | 2003 |

| Stagni Cup | Handicap | Top | 1950 |

| Swiss Championship | |||

| Symonds Shield Cup | |||

| Lord Trenchard Inter Services Championship | |||

| University Challenge | Team Handicap | Junction | 1994 |

| Aris Vatimbella Cup | Handicap | Top | 1964 |

| Willoughby Cup | Open | Junction | 2002 |

| World Championship |

Timekeeping and Starting

Every ride on the Cresta Run is timed - both practice runs and in races. Over the years, the way of testing the time it takes a rider to get from Top or Junction to Finish, has developed to become more and more precise. In 1893, one man acted as both starter and timekeeper. He stood in line with two posts on the 'Timing Line' and signalled to the rider to begin - who could do so in any way he chose; the clock was started from the moment the toboggan crossed the line.

His position is perfect and in a second or two he will be going fast.”

-

1/6Everybody's. “General Ames makes a cautious start from Junction“ 1951.

-

2/6Everybody's. “John Crammond, Britain's leading rider“ 1951.

-

3/6Everybody's. “John Crammond, turns to the right by pushing the skeleton round with his left arm and shoulder“ 1951.

-

4/6Everybody's. “This rider is now turning safely on Shuttlecock.“ 1951.

-

5/6Everybody's. “After Shuttlecock comes Stream Corner, and then the straight“ 1951.

-

6/6Everybody's. “At speed on the horrifying 1 in 2.8 gradient of Church Leap“ 1951.

From 1885–1895 two synchronized clocks with a timekeeper each, were placed at the start and at the finish. Riders were sent off at one minute intervals. The starter stopped his watch when, at the end of the run, the flagman dropped his flag as the rider crossed the finish line. At the end of the race, the starter compared notes with his colleague. This system lacked precision and in 1895 John Baird installed a chronograph and timing became accurate to within one tenth of a second. An electric stopwatch with two threads, one at start and the other one at finish, started and stopped the watch when the rider broke it. Nowadays, an electronic timer-sensor is used.

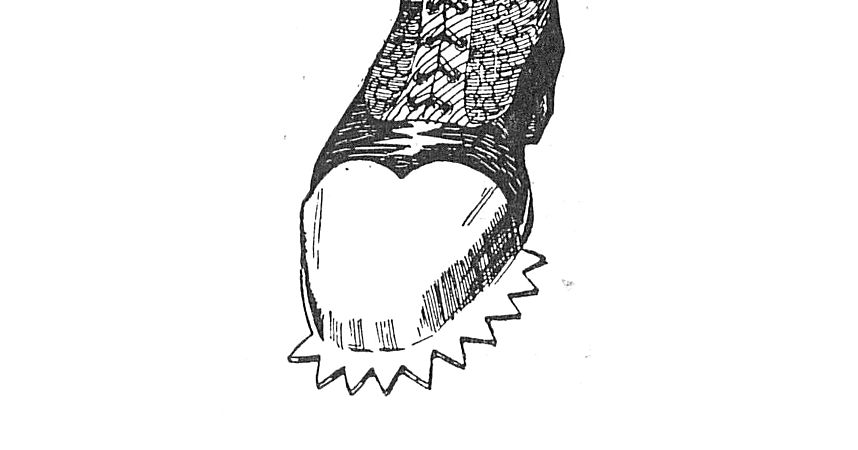

In the early days it was suggested in the local press that the future of tobogganing will be a question of "boots". It was argued that as the feet are used to control and brake, then those with larger feet have an advantage, and that in future toboggan handicaps will be arranged by the size of the boot rather than by an allowance of time.

See also in-depth information about the history of timekeeping on the Cresta Run from OMEGA watches.

Records

The first rider ever breaking the 50 second barrier from Top was Lord Wrottesley with the World Record of 49.92 seconds on 1st February 2015. At the same time, Lord Wrottesley achieved the World Record of 82.87 mph. CONGRATULATIONS! Prior record holder with 50.09 seconds has been James Sunley for 16 years. The current record from Top is 49.92 seconds, held by Lord Clifton Wrottesley. The current record from Junction, held by Johannes Badrutt, is 41.02 seconds. Nino Bibbia won the Grand National 8 times and so did Franco Gansser.

Assured facts about the cresta

- Overall distance (Top to Finish) 1212m (3977ft)

- Overall drop (Top to Finish) 157m (514ft)

- Overall gradient (Top to Finish) 1:8.7 to 1:2.8 (avg 1:7.7)

- Distance from Junction 890m (2921ft)

- Drop from Junction 101m (332ft)

- Gradient from Junction avg. 1:8.8

- Record holder from Top: James Sunley 50.09 s

- Average speed: 53 mph (85 km/h)

- Speed at Finish: close to 80 mph ( 128 km/h)

- Record holder from Junction: Johannes Badrutt 51.02 s ( beginners need from Juction about 65-75 s. )

- Fall ride ratio: 1:12

- Average speed: 56 mph

- Over 30 races per year

- Statistically, …playing marbles (is) more dangerous than riding the Cresta Run (source: www.countrylife.co.uk)

- (One) German man, (who came straight from Drake’s) proceeded to ride naked. The reaction of some members was simply surprise that his time wasn’t quicker due to lack of drag

- (a) rookie German rider (…), overcome with fear, ran off up the mountain. ‘To the German man running up the hill,’ announced the tannoy, ‘we at the Cresta do not mind if you are scared, but may we please have our helmet back?’

- Errol Flynn posted the slowest time ever on his first ride: 368 seconds. Supposedly, he’d stopped on the way down, which is the only explanation for such a high time.

- The Cresta is one of the few sports where dressing time dramatically exceeds playing time

- There is a horse in the Shuttlecock Club which also attended the Shuttlecock Club dinner in the year it fell near Shuttlecock

- Before the advent of motorcars and aeroplanes, the Cresta riders were the fastest men on earth. (source: www.forbes.com)

- The first Viscount Trenchard, semi-paralysed from a bullet wound from the Boer War, crashed on The Cresta and found his spine had readjusted and his injury had gone. (from How David Gower got it in the neck on a daredevil descent of Cresta Run – Richard Wolliams, 06/2013 www.theguardian.com)

- The first Lord Brabazon of Tara was 71 years old when he won the Cresta’s Coronation Cup in 1955 at a speed of 44 mph, and went down until his 80th year.

- In the early days riders would have to walk nearly a mile from Finish to Top and their heavy toboggans would be pulled back up by Arbeiters to Junction, on large selds, then one by one on foot to Top. Nowadays a truck is used called a ‘camion’

- Forces of up to 5Gs can be encountered on turns (Nicolas Niarchos 17/01/2014 nytimes.com)

- Ronnie Rae – a secretary of the club and famous for his announcing style. If he started an announcement about a time with three ‘Hellos’ it meant a very impressive run.

- If you are late for your slot then you are disqualified from racing.

- The ‘Five-O Club consists of riders who have broken 51 seconds from Top. This was first done in 1987 by Franco Gansser

- Prince Constantin of Liechtenstein rode in the Seniors race aged 88

- Bruno Bischofberger once went down the run barefoot and another time with fireworks on his back

- The ‘East West’ race is supposed to made up of teams from the Western and Eastern hemispheres. The losing team has to pay for caviar and champagne for the winners.

- Miss Ursula Wheble, one of the best lady riders, summoned Vera Barclay to see her in 1913 to ask her to moderate her language lest she give lady riders a bad name

Laudable riders, famous people and others

- A

- Abercromby, Captain R. O.

- Adams, Franklin

- Agnelli, Gianni of Fiat

- Ames, General Lawrence

- B

- Badrutt, Caspar - founder of Palace Hotel

- Badrutt, Johannes - founder of winter sports tourism and the Kulm Hotel; built the first Cresta Run in order to prevent accidents through his hotel guests sledding down the icy streets of St. Moritz endangering each other and civilians alike; won the Grand National in 1990 and 1995; won the Grand Slam in 1995

- Badrutt, Peter

- Baines, Trevor – guru

- Baracchi, Nico - won the Grand Slam in 1982

- Bardot, Brigitte - handing out the race prices to the winners at the Kulm Hotel

- Bass, Gaudens

- Bathurst, Hiley Ludlow

- Bathurst, Ludlow

- Beinecke, John

- Berchtold, Poldi

- Bertschinger, Christian - won the Grand Slam in 1992; Five-o club

- Betts, Paul - performed a handstand on his toboggan while sliding down Junction straight

- Bibbia, Eddi - cousin of Nino Bibbia

- Bibbia, Gianni - son of Nino Bibbia

- Bibbia, Lorenzo

- Bibbia, Nino - local St Moritz Greengrocer, and one of the best riders. He rode the Cresta more than anyone else - apparently 3,000 times, and won over 400 prizes on the Cresta. He won an Olympic gold medal in the 1948 Winter Games for Skeleton. He competed in many winter sports and won over 230 gold medals in his career. He died at age 91 in 2013. A German newspaper called him 'Der Skeletonkoenig von St. Moritz' - the king of the skeleton bob

- Bischofberger, Bruno - although better known as a Swiss Art Dealer, he was an exceptional Cresta Rider in the 1970's and pioneered the 'kamikaze' position - where the rider has his hands by his sides, sacrificing control for speed; introduced the Kamikaze position and speed suit after putting himself atop his toboggan into a wind channel, first rider to win the Grand Slam (in 1972)

- Board, Julian 85

- Bohlen und Halbach, Claus von – member; son of Arnold von Bohlen und Halbach

- Bohlen und Halbach, Dominik von - son of Arnold von Bohlen und Halbach

- Bohlen und Halbach, Eckbert von - instructor

- Bond, James - went down a Cresta Run lookalike in: “On Her Majesty's Secret Service”

- Bonorand, Peter - designed the first Cresta Run back when he was a 22 - year old geometrician

- Boorum, Charles Lowe - he was thrown 40 feet in the air, turning a complete somersault and fracturing his scull in his fall at Shuttlecock

- Bott, John Arden - inventor of the sliding seat for toboggans

- Brewster, Reverend Lester - assistant secretary

- Brown, Murray

- C

- Cattaneo, Giancarlo - Five-o club

- Child, L. P. - introduced the »America« toboggan model

- Coles, Bruce

- Connor, Doug W.

- Cornish, Mr.

- Cowell, Dick

- Crawford, Jack - one of the six riders over 70 who have ridden from Top

- Curzon, Frank

- D

- Daintry, Garry

- Dalmeny, Lord Harry

- Dawson, Matt - Rugby player, rode the Cresta in 2010. Flew out at Shuttlecock.

- De Boer, Lambert

- De Bylandt of Holland, Count Jules - died after he slammed into a plank that crossed the run at Junction Start. It was the first run that day and the Arbeiters had forgotten to remove the plank. De Bylandt insisted on going before another rider who was originally supposed to go first that day.

- De Verdon Wrottesley, Baron Clifton Hugh Lancelot - Five-o club

- DiGiacomo, Michael - author of the wonderful and outright book about the Cresta, »Apparently Unharmed«

- E

- Edward, Prince

- Erdmann, Victor - shuttlecock president in 1995

- F

- Felder, Paul - won the Grand Slam in 1974

- Fischbacher, Christian - honorary Life President; won the Morgan Cup five times

- Fischer, Marc

- Fiske, William 'Billy' - one of the greatest riders, an American, was just 16 when he captained the winning American bobsled team in the 1928 Olympics in St. Moritz. He notably never flew out at Shuttlecock. He died in the Battle of Britain in August 1940. Lord Brabazon wrote in an elegy for The Times, "We thank America for sending us the perfect sportsman. Many of us would have given our lives for Billy, instead he had given his for us."

- Flynn, Errol - recorded the slowest time ever (368s from Junction in the first ride) - apparently stopping at Shuttlecock to drink champagne, and disappearing immediately afterwards

- Freeland, Anthony - first man to go over the top of the final finish bank; dropped 16ft. into a concrete parking lot; seriously hurt, recovered and resumed riding

- Freytag, Daniel

- G

- Gansser, Franco - a rider in the 1980s and 1990s, won the Grand National six years running and many other races. He held the record from Top until 1992

- Gansser, Franco - won the GN 8 times; won the Grand Slam in 1988; Five-o club;

- Gansser, Reto - brother of Franco Gansser

- Glander, Paul – guru

- Glattfelder, Tazi - founder and owner of »Glattfelder Caviar«

- Grandi, Willi

- Green, Andy - members of the British armed forces; star as RAF fighter pilot and World Land Speed Record holder; Squadron Leader

- Green, Squadron Leader Andy - RAF fighter pilot and World Land Speed Record holder, who when asked what setting the record was like, replied "Like the finish of a really quick run down the Cresta."

- Gurus - Trevor Baines, Paul Glander, Arnold von Bohlen und Halbac

- H

- Haeberli, Adolf

- Hazlerigg, Tom - one of the six riders over 70 who have ridden from Top

- Heaton, Jennison

- Heaton, Trowbridge

- Hitchcock, Robin - "anonymously" donated the stove in Top Hut

- Hotz, Edi

- J

- Jackson, Mark

- Jackson, Sir Mike

- Joos, Gregor

- K

- Kaegi, Gottfried - finished 5th in the 1948 Olympic race; one of the six riders over 70 who have ridden from Top

- Kefalas, Alexandros - took part in the 2014 Olympics and grew up near St. Moritz. He became interested in the Cresta after working on the door of The Dracula Nightclub

- Kelly, James

- Kennedy, John F. – see President

- Kennedy, Joseph P. – see President

- Kennedy, President John F. and his brother Joe, Jr. - riders

- Kidd, Billy - US ski team downhiller, did it in 51 seconds

- Knight, Edward

- L

- Latscha, Patrick - hit a deer in the Cresta Run, both stayed mostly unhurt invented the »string-pull start«, which was banned shortly after

- Latscha, Walter

- Learco Bernasconi

- Liechtenstein, Prince Constantin of

- Lord Benjamin

- Lord Christopher

- Lord Derek

- Lutz, Bob - auto industry figure

- M

- MacCarthy, Fairchilds - important club secretary for 23 year (1948-1971); "Mac, you have not only been the driving force and the charm of the Cresta - for us you are its soul" (Gunther Sachs)

- Marenzi, Count Luca - fastest ever American rider; Five-o club

- Mathis, Peter-Christian

- Mathis, Reto - owner of Mathis's Food Affairs

- Mettler, Markus - Five-o club

- Monacco, Prince Albert von – rider

- Moore-Brabazon, Charles

- Moore-Brabazon, Lord John Theodore Cuthbert - one of the six riders over 70 who have ridden from Top

- Morgan, Harry Hays - an American - began riding in 1924 and was SMTC president for six years - one of only two non-British presidents.

- N

- Nater, Christian

- Nater, Urs

- Neilson, Rory - died in 1973 after he was struck by his toboggan at Shuttlecock

- Nelson, Gurner

- O

- Oppo - horse

- P

- Payne, David

- Pennell, Captain Henry - succumbed to internal injuries in 1907 after falling at Shuttlecock

- Pitsch, Giancarlo - in the barroom of the clubhouse is a helmet which Pitsch had cracked in a Shipton-Stoker; Five-o club; won the Grand National in 2000

- Prade, French Tycoon

- Prade, Jean-Noel

- R

- Raab, Stefen - German TV presenter

- Ramsay Rae, R.A. - an Australian pilot who became part of the RAF Cresta team, became club secretary

- Rayner, Nick

- Ribbentrop, Dominik von

- Rutherford Heaton, John - finished second in both (1928, 1948) olympic Cresta races;

- S

- Sachs, Gunter - a wealthy German industrialist and playboy from the seventies, was married to Brigitte Bardot. He founded the Dracula Club - a Cresta legend

- Schnyder, Rolf

- Schueler, Dennis

- Schwarzenbach, Urs - went over the last bank plowing headfirst into the Camion; his toboggan hit the Camion driver and another rider.

- Sharrigan, Chris

- Sharrigan, John

- Sheppard, Anthony

- Shields, David

- Shields, Larus

- Shuttlecock Club member - fell near Shuttlecock and attended the dinner that year.

- Sunley, James - he is the former record holder at 50.09 seconds from Top and current president of the SMTC

- T

- Tara, 1st Lord Brabazon of - president of the SMTC from 1939-1954

- Tara, 2nd Lord Brabazon of - came to St.Moritiz consistently from 1911 until his death in 1974.

- Tesdorpf, Carl - Five-o club; ran down the Cresta on the mini toboggan shaped clock from the bar at the Steffani Hotel in around 66 seconds from Junction

- Theler, Cha Cha

- Thoma-Badrutt, E. - an excellent athlete and a citizen of St Moritz, Thoma played an important role in the Cresta Run. He was secretary of the Kulm Hotel.

- Trudeau, Pierre - Former Canadian Prime Minister, did the Run in 65 seconds

- V

- Vatimbella, Aris

- Von Bohlen und Halbach, Arnold - guru instructor, nickname “German aristocrat”

- W

- Weissmann, Freddie

- Wheble, Miss Ursula - excellent rider and bobsleigh crew member. She won the Ladies Grand National 9 times and was awarded her colours in 1905. Competing against men in 1908, she won the Bott Handicapp and came fourth in the Grand National on level terms.

- Williamson, Sir Brian - SMTC president from 2009 to 2014

- Willoughby, Lt Col. Digby J. - Club Secretary - flown out at Shuttlecock more than 50 times - the record. He endeared himself as club secretary with his amusing announcements over the tannoy, including concluding the days riding with 'Terminato!' He also used to play themed music during pauses, after someone had fallen.

- Wilson, Doug

- Woodall, Jonnie

- Worner, Manfred former NATO secretary

- Wrottesley, Lord - the first rider ever breaking the 50 second barrier from Top with the World Record of 49.92 seconds on 1st February 2015. At the same time, Lord Wrottesley achieved the World Record of 82.87 mph. Wrottesley won his Cresta colours in 1996 and has won many of the Open races since his first victory in 1997. He has won The Curzon Cup a record 9 times, The Morgan Cup a record 11 times (equalling Franco Gansser's record), The Brabazon Trophy a record 14 times and the Grand National a record 11 times. He has also won The Grand Slam a record 5 times. He holds the record for the number of Classic races won with a total of 44 to date and the Flying Junction Record of 31.44 seconds

- Wynne, David - creator of the bronze Rider sculpture standing across the street from Kulm Hotel

The St moritz tobogganing club (SMTC)

The principal activities of the SMTC are "...the conduct of races and practice on the Cresta Run and the encouragement of tobogganing generally...". The St Moritz Tobogganing Club membership includes e.g. English lords, Italian counts, German princes, architects, surgeons, real estate executives, butchers, art dealers, greengrocers and retired hair dressers. It is principally British, and only two of the presidents in 130 year have been non-Brits. English is the common language. The SMTC is run on an entirely amateur basis and thus none of the office-holders or instructors, often termed 'Gurus', who initiate the beginners before dawn, receive any payment for their services.

Membership

The SMTC is a members-only club, and reviews up to 50 applications a year, about half of which are granted. In 1908 there were only 65 members, including 21 women, and fewer than 60 riders. In 1974 this figure was 900 members. The present membership is approximately 1300. Decisions about who to grant membership to are democratic and based on both riding and social criteria - as it should be in an amateur club. Indeed one member, Adolf von Ribbentrop, was the grandson of Hitler's foreign minister. In an interview in 1975 for Sportsillustrated, Lord Brabazon had the following to say:

"...if a man's technical qualifications as a rider are equal and no one says he's a bloody bore or another kind of bounder, if he's a good drinker and a good bloke, then he'll be in, won't he? There is room for all kinds - we need occasional clowns, you know, to keep it all alive, all going, and one fellow who is not a very good rider but in a very loud way is good fun will be elected quite without trouble."

However, any man over 18 years and with insurance can ride the Cresta. After completing the beginners course, which includes three to five runs from Junction, a Beginner becomes an SL Rider. SL means Supplementary List, from which the actual members are elected on application. Members can ride anytime, while SL Riders, as well as Beginners, have to register before they can ride. Members have priority.

When I entered the clubhouse, my first impression was that it was like a rowing club or a traditional golf club such as the R&A in St. Andrews. (Matt Dawson, Rugby player dailymail.co.uk 02/2010)

Presidents

- 1887–1899

- Major W.H. Bulpett

- 1899–1904

- Hon Harry Gibson

- 1904–1905

- Captain Bertie Dwyer

- 1905–1919

- Major W.H. Bulpett

- 1919–1922

- Hon Francis Curzon Disciplined and autocratic, but effective and devoted to the run

- 1922–1924

- Leland H. Littlefield

- 1924–1933

- Hon Francis Curzon

- 1933–1939

- Harry Hays Morgan

- 1939–1954

- Lt Col J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon MP MC - 1st Lord Brabazon of Tara

- 1954–1956

- Sir James Coats Bt

- 1956–1958

- D.W. Connor DFC

- 1958–1963

- Viscount Bledisloe QC

- 1963–1968

- 2nd Lord Brabazon of Tara CBE

- 1968–1973

- Sir Dudley Cunliffe-Owen Bt

- 1973–1978

- R.G. Gibbs

- 1978–1984

- Air Vice-Marshal R.A. Ramsay Rae CB OBE

- 1984–1985

- R.G. Gibbs

- 1985–1991

- John K. Shipton

- 1991–2004

- Viscount Bledisloe QC

- 2004–2009

- C Julian Board

- 2009–2014

- Sir Brian Williamson

- 2014–

- James B. Sunley

Disputes in the smtc

As in any long standing amateur club with colourful personalities and enthusiasm for their chosen passion, there have been disputes. These are covered in detail in 'The Cresta Run' by Michael Seth-Smith, complete with fascinating letters between various renowned club members. Notable disputes include:

In 1930, a secret meeting was held to try to get rid of the current president Curzon - neither the president nor the vice-president were present. Curzon was seen as autocratic and that he acted like the Cresta Run belonged to him. He did not grant permission when members wanted to open the run from Top and did not take the committee into account when making decisions. A series of dramatic telegrams ensued, but Curzon retained the presidency.

In 1954 an 'International Championship' under the auspices of the Fédération Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing was proposed and the suggestion had internal repercussions to do with the uniqueness of the Cresta Run and its not being recognised as an 'International' sport, the British nature of the SMTC and unnecessary rivalry.

The Genesis of the Cresta Run in St. Moritz

You will find here a brief history of the early days of

the Cresta Run and a timeline.

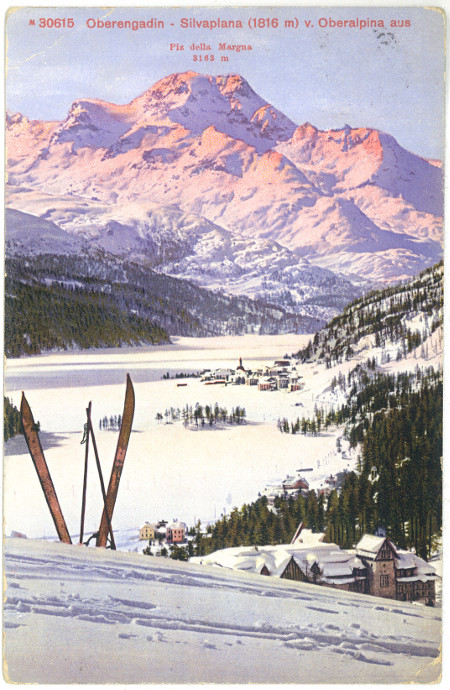

St. Moritz is located high in the Alps, in the

south east of Switzerland in the Engadine Valley. Dating

from Roman times, it has an average of 322 days of

sunshine a year and a dry invigorating climate. It was

in this area of Europe that winter sports, at the end of

the 19th century, developed and turned into what we know

today. The Cresta Run and the people associated with it

in St. Moritz were instrumental in this remarkable

development.

I do not speak lightly of happiness, but I believe I am close to it here. Thomas Mann

How winter sports began in the Engadine Valley

The history of the Cresta Run is tightly connected to the history of winter sports in Switzerland in general. The story goes that in the autumn of 1864 hotelier Johannes Badrutt invited four of his English guests to spend a winter in St. Moritz. He promised them they would enjoy the winter in the Engadine much more than in England and made a tempting proposition: Badrutt would offer them a stay at his hotel (The Kulm) free of charge for the entire winter and if the weather conditions on their arrival were not to their liking, he would even pay for for their return fares to London. The four men accepted and arrived at St. Moritz under a clear blue sky, regretting that they had not brought sunglasses. Needless to say, Badrutt’s new winter guests were excited about the splendid possibilities offered by the winter weather in the alps, and they went home far more enthusiastic than they had been at the start of the winter. They returned the following winter, bringing some of their friends who had become curious after hearing stories about winter holidays in Switzerland.

Badrutt was a skilled innkeeper and knew how to please his affluent British guests and so attracted a growing stream of visitors by providing them with any luxury and comfort they liked. Add to this the beautiful weather, winter sports and other outdoor activities, The Swizz alps proved more appealing than England during winter . One of the activities the English found for their amusement, was sledding.

-

1/12St. Moritz

-

2/12Watching the start of a race

-

3/12Second Bank of “Church Leap“, St. Moritz.

-

4/12Riding “Church Leap“ - a foretaste of the later joys and perils of the Cresta.

-

5/12The Village Run

-

6/12The Village Run - The Start

-

7/12The Village Run - Lord William Manners and the Hon, Harry Gibson on Rocking-Horse Toboggans

-

8/12The Village Run - Caspar's Corner

-

9/12The Cresta Run, St. Moritz - The Start

-

10/12The Cresta Run, One Tree Leap and Terrace Crow's-Nest for Time-Keeper

-

11/12The Village Run - Church Leap

-

12/12From 1885. “The Strand Magazine“. The Cresta Run – Bobsleigh turning a corner on the high road.

They borrowed toboggans – which were very common in the alps for winter transportation – from the villagers and raced down the icy streets of the village, endangering each other as well as uninvolved pedestrians.

In the adjacent village of Davos, sledding was practised on a more professional level. There was the so-called 'Village Run', a prepared tobogganing run on which the first 'International' race took place in the February of 1884. Along with Germans, Dutch, Australian and other Swiss, the guests of the Kulm Hotel in St. Moritz participated in this race but were beaten by their opponents.

In the autumn of the same year, Peter Badrutt and the Outdoor Amusements Committee of the Kulm Hotel decided to build their own skeleton run and to invite the Davos enthusiasts for a return match. They engaged the 22-year-old geometrician Peter Bonorand, who had just returned from university in Zurich to his home of Celerina, to draw the plans for the first Cresta Run. After discussing the plans with the committee, the outline of the run was marked with wooden posts in autumn and after the snow had fallen by December, the St. Moritz enthusiasts built up the run and invited their Davos opponents for the first 'Grand National', which was to be held on 16th February in 1885. The first three finishers were from Davos and so the St. Moritz team was defeated again, but this time on their own course.

In February of 1886, the second 'Grand National' was held on the Cresta Run and was also won by Minsch, from Davos. The third race in 1887, saw Mr. Cornish come down the run head-first - a method adopted in subsequent years by all riders. It also saw the favourite, Minsch disqualified for having had a practice run, and the 14 year old Bertie Dwyer breaking the two minute barrier. Davos won for a third year, but never again.

Since those early days the Cresta Run has enjoyed similar dramas, friendly rivalry and developed into a sport that whilst 'amateur' in the best sense of the word, has produced world class athletes. Indeed soldiers see the Cresta as an important part of their training and the inter services cup is held each year.

The Timeline

- 1864

- Johannes Badrutt, St. Mortiz hotelier, convinces four British guests to holiday in winter

- 1869

- Dr Alexander Spengler publishes pamphlet recommending tuberculosis sufferers spend the winter in the Alps.

- 1882

- Beginning of the Skeleton sport: L.P. Child (from New York) drives down the street from Davos to Klosters on a 'made in USA' imported wooden toboggan

- 1883

- John Addington Symonds founds the Davos Tobogganing Club

- 1884

- Kulm Hotel outdoor sports committee is formed

- 1884

- The first Cresta Run is built by Major W.H. Bulpetts

- 1885

- The first 'Grand National' race is held on 16th February, between 10 riders each from Davos and

St. Moritz - 1887

- The St Moritz Toboganning Club is founded

- 1887

- The 'America' toboggan replaces the luge

- 1887

- Mr. Cornish is the first person to go down the run head first in the Grand National

- 1889

- Monetary prizes for winners are stopped, ensuring the sport remains inclusive and amateur

- 1890s

- Caspar Badrutt enlarges the Beaurivage Hotel and renames it the Palace Hotel, in recognition of the increasing number of visitors, and serious sports enthusiasts as well as invalids.

- 1893

- First ski race, near St. Moritz

- 1895

- The Cresta Run is timed electronically - John Baird develops the Chronograph and timing of runs became accurate to within a tenth of a second

- 1896

- St. Moritz Bobsleigh Run

- 1896

- First "Ladies Grand Nationals" in St. Moritz, last one was held in 1921.

- 1899

- The Kurverein pays for the proposed Engadine Railway to be diverted to protect the Run and also to build a bridge across the Run

- 1901

- John Bott invents the Seat on Rolls

- 1902

- The sliding seat is added by Arden Bott

- 1904

- The railway to St. Moriz is completed

- 1905

- The Bott Cup - the first handicap race

- 1907

- Two deaths - 9th January, Captain Henry Pennell fell at Shuttlecock and died from his injuries

- 1907

- Count Jules de Bylandt, hit a plank which had not been removed from the run at junction

- 1910

- The Curzon Cup

- 1913

- Charles Lowe Boorum Jnr, fractured his skull in a fall at Shuttlecock and died

- WAR

- 1925

- Mrs J.M. Baguley wins is the last woman to race on 13th January

- 1928

- The 2nd Winter Olympics are held in St. Moritz. The Cresta Run is an official event, won by the Heaton brothers, and and Billy Fiske, aged 16, wins with Bobsled team

- 1929

- Women are banned from riding the Cresta on the 6th January

- 1932

- A road bridge is built over the Cresta

- 1933

- The handbook 'Hints to Beginners on the Cresta' is written

- 1934

- The Shuttlecock Club is founded and the inaugural dinner held

- 1935

- The Morgan Cup

- WAR

- 1948

- The Winter Olympics - Nino Bibbia wins gold for Italy

- 1955

- The Cresta is opened again after an eight year gap. On January 3rd this season it is open from Stream, the lowest section in its length, and from Juction on January 8th. The Top is open last.

- 1955

- 71-year old Lord Brabazon wins the Cresta Run Coronation Cub at an average speed of

44mp/h (71 km/h) - 1964

- The clubhouse is built

- 1966

- Brabazon Trophy

- 1973

- The 4th death - of LT Rory Neilson

- 1974

- Gunter Sachs opens the 'Dracula Club'

- 1979

- 19 years old Marcel Melcher wins the Grand National as the youngest winner

- 1985

- The Cresta Run centenary

- 2002

- 8 times Grand National Winner, Lord Wrottesley, finishes 4th at the 2002 Olympic Winter Games; there have been around 11,000 rides down the Cresta this season and the vast majority

were injury-free. - 2010

- 100th Grand National on 13th February

- 2010

- Cresta Run celebrates 125 years

- 2012

- Surveillance cameras are fitted for safety and to broadcast races live

The Cresta and its Secrets: Traditions, Myths and Anecdotes

Sports and the clubs that attend them often build up practices and traditions that reflect the people involved. The Cresta Run certainly has its fair share. The SMTC has always been a very British club - only two of the presidents have been non-British. Indeed Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (from the foreword of 'The Cresta Run' by Michael Seth-Smith), says:

It seems to be a characteristic of the British to take a perfectly ordinary, even juvenile amusement and convert it into a highly organized, competitive sport or recreation Prince Philip

It has attracted the aristocracy and the military - but also local people and a range of enthusiasts from across the globe. Whilst there are plenty of rules to ensure safety is given the highest importance, there are also many other more quirky traditions and customs which have grown up around the sport. And of course – urban myths!

- Gunter Sachs is said to have run the Cresta in a coffin secretly at night

- It's claimed that, at various stages in the run's 125-year history, every bone in the human body has been broken by riders who fail to complete the run successfully

- Cresta's house drink: Bullshot (a blend of vodka and consommé)

- Digby was said to have made secret parties, "Unmentionables" in his room in the basement of Kulm Hotel

- Several skeletons are said to have been loaded onto the Camion with wet seats and no rider willing to claim its ownership

- Trevor Baines intentionally fell at Shuttlecock the very morning of the Shuttlecock Club dinner in 1992 over which he was to preside, as there was no proof he’d qualified for the Shuttlecock Club until that day

- Apparently, Errol Flynn recorded such a slow time because he stopped for a glass of champagne at Junction with a beautiful woman.

- In 1913 the numbers of riders were increasing, necessitating an improvement of the facilities. A cricket pavilion was brought over from England.

- 'The Firework' - Members imitate, en masse, the noise of a firework for Cresta winners - invented by Sergei Ovsievsky at a Palace Hotel dance

- If you fall at Shuttlecock you are expected to stand up promptly and wave both hands in the air to signal the next rider can start. If you have broken an arm you are expected to wave the other.

- “One New Year’s Eve I went straight from Drac’s down to the Cresta Run and got on my sled still wearing my tuxedo. It was a great way to start the New Year.” Alessandro Gatti

- Cresta Kiss – get in touch with the ice wall

- A SMTC member, Adolf Haeberli, a retired hairdresser from St. Moritz, wears a ZZ Top–like beard and occasionally descends the run in a protective suit with fireworks sparking off his back.

- Nino Bibbia, one of the greatest Cresta riders, apparently started riding when he swapped a case of Chianti on his horse-drawn grocery cart, for a skeleton bob. He went on to win gold in the 1948 Olympics.

- The Morgan Cup is filled with champagne to be passed around at the prize-giving - apparently paid for by the winner.

- Apparently if a rider has broken a rule, he often meets with misfortune - a fact that is put down to 'the power of the tower'

- Fairchilds MacCarthy, a club secretary, once yelled "Who do you think you are!" to a rider who came to the Tower to pay his bill, only to find out it was His Royal Highness the Duke of Kent.

- One rider in the seventies wore all the required clothing - metal rakes, hand guards, elbow and knee pads etc. - and nothing else...

- The twelfth place finisher in the Heaton Cup treats the other eleven riders to all the bratwurst (grilled sausage) they can eat.

- The son of Gunter Sachs - Rolf, sponsors a 'tea tray' race and a night-time race.

- Three young men age 17-21 got seriously hurt while driving down the Cresta Run on a snow shovel. A wooden beam made them suddenly stop after a 500m ride at high speed. One of them got seriously hurt at the head and needed to be transported later with a helicopter to a special hospital.

- An Army captain survived a six month tour of Iraq unscathed only to have his leg torn off attempting the famous Cresta Run in Switzerland.

The Shuttlecock Club

So called one imagines either because it is shaped like the end of a shuttlecock, or one flies out in imitation of an airborne shuttlecock, this club was founded in 1934, and automatic membership is afforded to those riders who fall at the infamous bend. They are entitled to wear the Shuttlecock Club tie and attend the dinners. The inaugural dinner menu included dishes such as 'Potage a la Piste' and 'Filet de Bouef Shuttlecock'. The club motto is " Here's to it, and do it, and do it again. If you don't do it when you come to it, you may not be able to do it when you want to do it again." Marilyn Monroe famously telegraphed the Shuttlecock Club with the words:

To members of your club you may have your curves but what about mine. Marilyn Monroe

Fascination Cresta Run

In the next paragraphs we want to deal with the question, why Cresta held the the imagination of so many famous men, creating an international fraternity unique in the annals of sport?!

"Why is it that men make their annual pilgrimage from all corners of the earth in an endeavour to conquer her? What causes such devotion? Each year men think that they have solved the mystery, and each year the Cresta remains an enigma, elusive, magnetic." (Quoted from the Epilogue of 'The Cresta Run' by Michael Seth-Smith 1975 - attributed to 'Tyke' Richardson)

The Cresta keeps it’s secrets a motto coined by the 1st Lord Brabazon

Spirit of comradeship

There is over a century of tradition associated with the Cresta Run and it is very much a family sport, which may account for some of the appeal - the same names appear in the races, and it is a father to son affair. There is even a 'father and sons' race and a 'brothers' race.

James Sunley, a champion rider, referred to the unique bond people who have been scared share, and it has even been compared to the fear soldiers feel during warfare - something unique to a particular group of people (Apparently Unharmed, Michael DiGiacomo, page 106)

"But the one thing that makes the experience of the Cresta Run and the atmosphere of the St Moritz Tobogganing Club truly unique is the comradeship that unites people of the most disparate nationalities, ages, professions, and social classes, whose taste for challenge forges friendships that last a lifetime" – Giovanni Agnelli of Fiat in the foreword of Michael DiGiacomo’s Apparently Unharmend

Inner Temptation

Because you’re crazy, that’s why. Because you’re nuts Jack Crawford, Rider

It is said that a desire to beat your own time is what makes riding the Cresta addictive and then you are under the 'Cresta Spell', and the rituals and traditions practised by the SMTC have been described as 'esoteric' – and one can understand this looking at the terminology, customs and behaviour associated with the Cresta Run. Michael diGiacomo writes in his book 'Apparently Unharmed': "...and indeed the Cresta has it dark side, too. I would say it took me a few years to get over my obsession with it. There were long stretches when a day didn't go by without my thinking about it..."

Barnaby Conrad said "I began to see the run as a crucible of fear, a kind of wine press of the human spirit that unites riders of different ages and nationalities. It was intoxicating." (http://www.forbes.com/forbes-life-magazine/2006/1211/156.html)

"I knew, in fact, that I could not win. It was a definite sort of knowledge - something I had only felt at routlette before." J.W.A. Woodall (quoted in sportsillustrated Every Man has a Mad Streak by William O Jonson)

The Cresta as a woman

The Cresta Run is regularly described as female – in the same way as a ship.

"For me she is an inspiration, and although I cannot claim her as my mistress, I shall remember her for ever."

– Michael Seth-Smith (The Cresta Run 1975)

"The Cresta is like a woman with this cynical difference – to love her once is to love her always."

– Lord Brabazon of Tara

"The Cresta is a powerful and attractive mistress. She will stand no nonsense when you are learning the ropes, and many and severe are the rebuffs that she administers to her ardent suitors."

– Jimmy Coats (The Evening Standard 1929)

Toboggans, riding and design

The Cresta is not a Slide. It is a Run and wants riding. A curling stone will not go to the bottom by itself, nor will you, if you don't do something on the way. FROM “Hints to beginners on the cresta”

Evolution of the sled

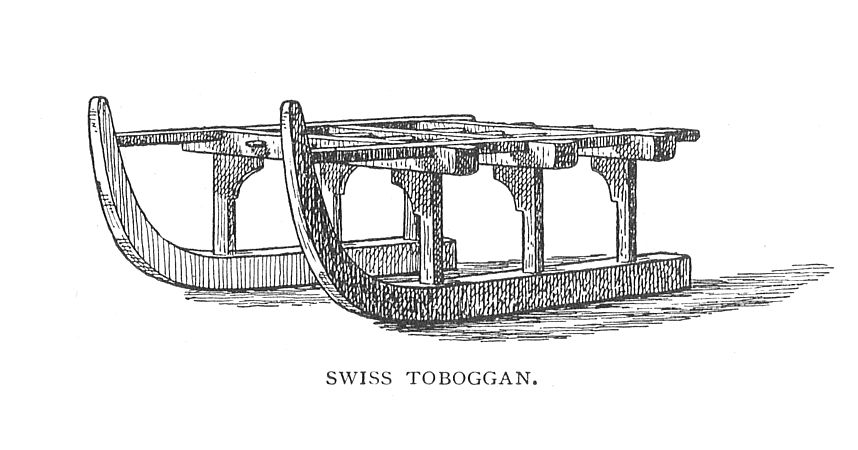

The following illustrations are taken from an article entitled 'Tobogganing in the Engadine' by Celia Lovejoy, which appeared in The Strand Magazine in 1895.

Swiss Toboggan - Toboggan is the native Canadian word for sled. The original Swiss Toboggan, ' Handschlitten' in Swiss parlance, was originally used to convey goods across the snow. It’s a light, wooden skeleton with flat steel bands mounted on to the runners.

America - Invented in 1887, the so-called 'America' skeleton is simple, yet solid and heavy in construction and looks rather odd as it is quite long and low. But when it was discovered that in races no other machine stood any chance against it, all initial prejudices were dropped and the America immediately superseded the traditional swiss Toboggan. It’s called America because of the misconception that similar sleds were used by native Americans.

Skeleton Spring Runner - One year after the advent of the America, Mr. W. H. Bulpett brought out the Skeleton Spring Runner, an improvement on its precedessor. It took some time until it had developed into a proper replacement for the former, but from 1890 on, no races were run on anything else, as the Skeleton has various advantages due to its metal construction, mainly that it doesn’t shrink or warp like a wooden sled. Also can be made with very high accuracy and is therefore reliable. As of 2014, it is still the only type of toboggan that is used to ride the Cresta.

You cannot just lie on the toboggan. You must think and you must ride it. Arnold von Bahlen und Halbach

The Skeleton - Skeletons are ballasted with lead, 30-60kg, average 40kg, Skeletons have a special “sliding seat”, which makes it easier to slide back and forth on the toboggan and was invented by John Arden Bott. During the 1920s and 1930s skeletons became faster as the diameters of the runners was reduced and the chassis was shortened. Ball bearings were added to allow the seat to slide more easily used to ride the Cresta.

The Flattop - In 1982 Reto Gansser took skeleton without a sliding seat down the run, and times started going up. The experienced rider still needs to adjust position to control the toboggan, but the absence of the sliding seat means the Flattop is easier to control and much faster. It is also designed so the bow on the runners can be adjusted more easily. The Flattop is 4 feet long and has padding to keep the rider in the right place.

Experimental Toboggans - Cutaway - no rear chassis, meaning the rider can start from the back not the side. Also the toboggan is more flexible as a result. Griffins - a flattop divided down the middle with independent springs on each side

-

1/4At full speed; nearing the finish of the Cresta at a mile a minute.

-

2/4The pace increasing – taking a corner at forty miles an hour.

-

3/4The first corner – the pace as yet not very great

-

4/4A flying start on the Cresta

The head-first style was established by Mr. Cornish in 1886 and by the Grand National of 1890, all riders had adopted this style. Before that date, everyone rode in an upright position, sitting on the toboggan. The main techniques are covered in 'Hints to Beginners on the Cresta' first produced in 1933, and some of the basic ideas follow. However, this is not the forum to disclose this hard-won wisdom! Suffice to say, in the words of the former England Cricket Captain, David Gower

"You're balancing on an inch of metal and you control it by moving your head or shifting your weight. It's pure timing. The elite riders don't have to be 25 years old and in peak physical condition." (06/2013 www.theguardian.com)

The rules of the club forbid any mechanical braking or steering device. Therefore, in effect, when the rider pushes his weight forward, the seat slides up and the sled rides on the runners, going faster. When the seat is pushed back, the knives dig into the ice and control it in the turns, and keep it from skidding sideways. Apparently, your first ride is likely to be your safest, because you are trying to go slow. After that, as you gain skill and confidence, both your times and the likelihood of falls increase...

As the Cresta Run is all natural with no concrete structure it is never exactly the same from one year to the next. Riders need to learn the latest nuances of the track.

Starting

Lying Start - All Beginners start in prone position, lying flat, facing the ground.

Running Start - More experienced riders grasp the toboggan either side of the seat and run past the contacts, landing on the seat in a way that further movement is not required.

Steering

Before you enter a turn, the rider slides backwards on the sled, where the runners are sharpened, and shift their weight in the appropriate direction in order to steer. As soon as the rider leaves the turn, he pushes forwards on the skeleton again to increase speed. This is where the pro riders enter 'Kamikaze' position, where they lean forwards as far as they can, basically swapping control for speed.

Braking

The toboggan itself has no brakes, instead there are special rakes attached to the boots, which can be used to slow you down. In order to achieve that, one has to find the right angle between the rakes and the ice run, which is about 45°. If they stand too steep, the shoes will bounce off the track. Also, the positioning of the feet is important for successful deceleration.

Falling

It is important that if a rider falls at Shuttlecock, which is the most likely, that he pushes his toboggan away from him to one side, and protect the head with the arms. If falling on the Run, it is important to make sure the toboggan is in front.

Other adaptations to technique and design

Lord Bledisloe experimented with connecting the lead underneath the toboggan to the sliding seat - but it didn't work as it was too heavy. Henry Martineau designed a skeleton which dipped in the middle to lower the centre of gravity. Jack Heaton devised a toboggan with a single runner supported by two higher up runners. It did not make much difference. An engineer, John Savage, experimented with detachable runners of different sizes, depending on the softness of the ice. The downside was a loss of spring as these were due to the runners. Lord Bledisloe then invented pear shaped runners to solve this problem but the steel bent.

Bischofberger in the 1970s brought some new ideas. For example he noted that the sharpness of the rakes as they cut into the surface of the ice, slowed you down. So he made his shiny and polished so they glided on the ice. It saved one-tenth to one-fifth of a second per run. He also invented the 'Kamikaze Posture' - which means putting your hands back along your sides instead of keeping your elbows out with your hands on the runners, cutting down on air resistance. You effectively give up control for speed.

Bischofberger also started sticking his arm out full length ahead of his toboggan as he came to the sensors at the finish - saving one-hundredth of a second. Reto Gansser coated his runners with Teflon - proving unsuccessful, as it didn't stick. Carl Tesdorpf used chemistry to create a substance which made his runners more slippery - but the expense lead to it being banned.

Patrick Latscha tied cord between the handles of his flattop - this was also banned.

(Much of this information is sourced from Michael DiGiacomo 'Apparently Unharmed' and 'The Cresta Run' by Michael Seth-Smith)

Fashion & Race Gear at the Run

Clothing has developed over the years and many fast riders now wear 'condom suits' and 'go-fast' boots which are more like football boots with smaller rakes. The more modern boots are only allowed if someone has achieved a time of 58 seconds. "Gathered at the start,... the competitors resemble medieval men-at-arms with their spurs oddly fastened to their toes instead of heels. They wear crash helmets and goggles, chin guards, knee and elbow pads, and heavy gauntlets with metal discs strapped over the knuckles. Their ribs are well padded with sponge rubber. Five sharp steel teeth, called 'rakes' are screwed to the toes of their boots."

(Frank Horn, glowingrealm.com 10/2012). But let's take a closer look on the past and its heritage - the clothing development.

On my feet were placed the strangest shoes I ever saw

"Like a knight in shining armour, the only thing I was not provided with was a horse. On my head they processed, via a screwdriver, a helmet...Then came goggles. On each arm were strapped heavy leather pads from bicep to wrist. My knees were given the same care by an official dresser. I don't believe anyone could put on this paraphernalia by himself. On my feet were placed the strangest shoes I ever saw. The toes had steel rakes pointing forwards. That was when I knew I wasn't getting on a horse; stirrups point backward...The last part of the costume was a pair of aluminium gloves to protect my skin if I touched the ice wall of the run."

Richard A. Wolters (The Cresta Run: 'a man ought to know better' 17/11/1980 csmonitor.com)

-

1/31902 “Pearson’s Magazin”

-

2/3Cresta fashion label; established 1929, as Cresta Silks.

-

3/31902 “Pearson’s Magazin”

The compulsory equipment includes boots with metal 'rakes', knee and elbow pads, a helmet and goggles, gloves with metal hand guards, and no rings in case of crushed fingers. All riders are helped to dress in the changing room by an attendant - and these have been from local families connected to the Cresta for many years. For many years Lorenzo, Nino Bibbia's nephew was in charge of the changing room.

The Cresta has always attracted the aristocracy and the wealthy and stylish, and the fashion of the day has been reflected in photographs.

The following requirements to a Cresta rider’s garb date back to the late 19th century but are still relevant: "The question of suitable apparel for male tobogganers inspired an informative article in the Alpine Post at the end of November 1895: "Dress in tobogganing, as everything else, will necessarily depend in a great measure upon the individual taste of the wearer, but, in this case, he will do well to bear in mind at least three essential points in providing himself with an outfit. Firstly and obviously the dress must be warm, secondly it must not in any way hamper freedom of movement on the part of the rider, and thirdly it must be what I shall term ‘snow-tight’. The novice who gaily skids down an ice run in spotless collar and cuffs is apt to be rudely awakened to the force of my third point, when he takes a fall into two or three feet of soft snow."

"The Club provides you with gear that looks fit for a gladiator: full-face crash helmet; leather knee and elbow pads; hand guards covered with five-inch metal saucers to keep the ice from smashing your knuckles; and boots with metal spikes on the soles and what are known as “rakes” protruding from the toes. Some riders wear traditional tweed plus fours with wool socks and sweaters as if they are on their way to a grouse hunt. The younger racers sport the sleek Lycra “condom suits” popular with speed skaters. Motocross suits and jockey’s vests prevent broken vertebrae." Helmets were made compulsory by the committee during the 1923/24 season

"...the full members of the St Moritz Tobogganing Club (SMTC), who appear to have come directly from a fetish club, clad as they are in skin-tight shiny jumpsuits (designed, apparently, to reduce drag and aid acceleration). I also notice an English group wearing plus fours, and a German party dressed in lederhosen." (Ian Cowie, Cresta Run: St. Moritz on a teatray 11/2008)

Off the Run members tended to dress in traditional British clothing, for example, tweed plus - fours, long socks and hunting clothes. However, in 1975 William O Jonson wrote "The rest of their clothing is disreputable - soiled jump suits, old ski jackets, baggy ski pants, Levi's, moth-bitten sweaters, patched knickers. There is, as always, a raffish hint of the seedy daredevil in their appearance, a touch of the carnival motorcycle stuntman, the Roller Derby rowdy, even winterized Knievels. (Every man Has a Mad Streak - Sportsillustrated 1975). The Cresta has always attracted the aristocracy and the wealthy and stylish, and the fashion of the day has been reflected in photographs.

-

1/2From 1939. Picture. Famous Raymond Mays, Peter Berthon (Actors) in a skiing holiday in St. Moritz, in front of the Palace Hotel. The tuxedo & blouson are inspirations for the Sven-Holger collection.

-

2/2From 1951. Magazine “Everybody's“. Lord Brabazon, President of the Cresta, and Ted Bott, third generation of a famous Cresta Family, putting on their armour.

Firstly and obviously the dress must be warm, secondly it must not in any way hamper freedom of movement on the part of the rider, and thirdly it must be what I shall term ‘snow-tight’. (Alpine Post at the end of November 1895.)

In 2015 a lifestyle design fashion collection called “Sven-Holger” will be launched from the independent design brand ”Sven-Holger”, inspired by the Cresta sport and influenced by its over 130 years of fashion heritage. Sven-Holger is dedicated to the members and enthusiasts and offers a selection of limited edition luxury fashion products, designed for the rider's daily activities from race to ballroom. This small family-owned Atelier brand services the rider's needs by craftsmanship, functionality and natural composites like e.g. cashmere.

For more information visit https://www.sven-holger.com/.

In the 1960's the design label Cresta Couture offered a women collection still available as vintage.

The Death Lecture

For a beginner, there is a procedure which must be followed before riding the Cresta Run. "The death talk wrapped up, the disclaimer signed, the knee, elbow and gladiator-style knuckle guards strapped on, the crash helmet cranked tight and the steel-spiked shoes laced up, I lie prone on a 40kg tea tray, my chin inches from the ground. Every muscle is tense...Shivering with cold and fear, I grip my toboggan as if my life depends on it - which it does. And then the man removes his foot." Simon Usborne (Death or Glory:Simon Usborne rides the Cresta Run, 02/2010, The Independent)

All riders must become Supplementary List riders - a form of temporary SMTC membership, and follow the club rules. They are given a small red book entitled 'Hints to Beginners on the Cresta', first written in 1933, then the procedure that follows consists of:

Arrival and registration

By 7.30 am signup to the SL list

Dressing – this is done with help and takes at least 15 minutes. Riders without their own equipment borrow it from the club

Club Secretary's Safety Briefing. 'death talk' at the club house - including displaying a composite X-ray 'skeleton' to demonstrate the importance of being safety conscious, as well as rules such as contact with the control tower.

'School for Beginners' at Junction Hut. Instructions include advice on how to stay slow and in control, the geography of the Run, positions on the toboggan and other techniques.

Start from Junction

Procedure: lift your arm when you hear your name

A respectable time for a beginner is said to be 70-80 seconds. From now on the 'beginner' is deemed an SL rider.

-

1/3Start from Junction (Sven-Holger B.)

-

2/3Procedure: Lift your arm when you hear your name (Sven-Holger B.)

-

3/3A respectable time for a beginner is said to be 70-80 seconds. From now on, the 'beginner' is deemed an SL rider. (Sven-Holger B.)

Accidents & Injuries

Nearly every bone in the human body has been broken by riders at some time in its 130 year history. Some typical injuries happen when riding the Cresta, among them are: cracked ribs (common and painful), broken collarbones and arms, dislocated shoulders, the Cresta Kiss (no problem anymore since full-face helmets are mandatory), broken/severed fingers (sometimes the gloves and hand guards can’t save a rider’s fingers when he collides with the walls of the Cresta at high speed), the Cresta Elbow – the violent jiggling on elbow muscles caused a chronic injury, being hit by your skeleton – If a skeleton stays on the run without its rider, the tannoy announces "Achtung Schlitten! Achtung Schlitten!"

It's addictive – I have the X‑rays to prove it. Doug Walker

In over 500,000 rides there have been fewer than 28,000 falls and only four deaths. On average one ride out of every 1,000 ends up with the rider in hospital. Although these may be reassuring statistics, every rider with some experience knows that accidents will happen and stand-by clinics and a helicopter are nearby. Beginner's are shown a full human body made up of riders' X-rays of broken bones, during the 'death talk' – and of course they sign a waiver. The Death Lecture

As the run is built from scratch every year, some years feature more accidents than others. The 1999-2000 season was particularly difficult, it is said. Micheal DiGiacomo writes in 'Apparently Unharmed' that "Falls from Top increased 20 percent from the previous season, even though there were fewer rides from Top. "

Deaths

- 1903

- A 'well-known lady rider' crashed onto her head but was saved by the tightly coiled abundance of hair on top of her head which cushioned her fall.

- 1907

- 9th January, Captain Henry Pennell fell at Shuttlecock and died from his injuries

- 1907

- 18th February, Count Jules de Bylandt, hit a plank which had not been removed from the run at Junction - it was the first run that day and the Arbeiters had forgotten to remove the plank. De Bylandt insisted on going before another rider who was originally supposed to go first that day.

- 1913

- Charles Lowe Boorum Jnr, fractured his skull in a fall at Shuttlecock

- 1973

- Lieutenant Rory Neilson died as he was hit by his skeleton after going off at Shuttlecock

Injuries

- 1895

- 1895 M. de Mouzzilly collided with a sleigh in the days before the road bridge - these types of accidents were not uncommon, and firstly lead to the stationing of a man at the road, and later to the bridge being built.

- 1907

- Charles Knapp, lost an gold forear in 1907

- 1919

- in 1919 John Bingham pulled his glove off to find he had severed one of his fingers

- Daniel Freytag went so high on Rise that he crashed into Nani's Bridge and was in a coma for weeks.

- Anthoney Freeland was the first rider to go over the top of the finish bank. He dropped 16 feet onto concrete. He rode again.

- The first Viscount Trenchard, semi-paralysed from a bullet wound from the Boer War, crashed on The Cresta and found his spine had readjusted and his injury had gone. (from How David Gower got it in the neck on a daredevil descent of Cresta Run – Richard Wolliams, 06/2013 www.theguardian.com)

- 2008

- In 2008 Captain Bernie Bambury’s lost his right foot when it hit a marker post at 80mp/h

- 2009

- In the 1999-2000 season (see above) James Kelly came out over Brabazon and broke his pelvis resulting in major surgery.

- Lord Bledisloe, who once ran over his own hand, pulled off a bloodied glove, shook out a severed digit and declared: "Never mind. At least it's not my trigger finger."

- Three young men age 17-21 got seriously hurt while driving down the Cresta Run on a snow shovel. A wooden beam made them suddenly stop after a 500m ride at high speed. One of them got seriously hurt at the head and needed to be transported later with a helicopter to a special hospital.

Captain Bernie Bambury, 32, lost his right leg below the knee after he hit a marker post at a speed of up to 80mph on the 4,000ft-long tobogganing course in St Moritz. His leg was shattered and severed hundreds of yards from the finish. But the brave soldier, from 4th Battalion The Rifles, completed the run before asking friends: "Is my ankle broken?" He then heard the horrifying reply: "It's not broken, it's gone." The Army officer underwent nine operations by medics who tried to sew the limb back on but Capt Bambury was told it might take two years for him to walk again and he was unlikely to regain full mobility. As a result he gave the order for surgeons to cut it off, preferring the certainty of recovery with a false leg. Capt Bambury, who is based at Bulford in Wiltshire, said: "The overwhelming balance of medical advice was that amputation and a prosthetic limb would give me the best prospects for the rest of my life and the swiftest return to duty. "Keeping my foot could have taken up to two years to succeed with a minimal chance of success. I am looking forward to starting my rehabilitation." He has been treated at the Headley Court military rehabilitation centre near Leatherhead, Surrey, which has gained a strong reputation for helping those with multiple injuries and fitting soldiers with prosthetic limbs. A Ministry of Defence spokesman said: "This was a tragic accident and Capt Bambury has taken a brave decision on medical advice to amputate his foot. We hope he is able to make a swift recovery and wish him all the best for his rehabilitation at Headley Court."

The Cresta Run in the Media

Newspapers, magazines and new media have reported on The Cresta Run consistently since its inception, and it seems it never fails to fascinate both riders and enthusiasts as well as the general public. An archive of magazine and press articles can be accessed here.

Newspapers and Magazines

The Times published a letter as early as March 1876, on the pleasures and misconceptions of wintering in the Engadine Valley; The gloomy vaticinations with whihc the summer visitors discouraged our intention of wintering at the Hotel Kulm have been abundantly falsified.

It goes on to describe the wonderful climate, food, flora and entertainment of the region.

The Illustrated London News recommended St. Moritz as one of the favourite Swiss resorts for most and invigorating holiday in the world for those who live in the damp and comparatively sunless climate of Great Britain.

The alpine post

This local newspaper followed the rise of Winter sports and The Cresta Run closely. In 1887, it famously included the following account of the pivotal moment the head first style was adopted:

Mr Cornish caused the chief excitement in the race by riding his toboggan head first. To do this he lay his body on the toboggan, grasping its sides well to the front, his legs alternating between a flourish in mid air and an occasional contact with mother earth or rather father ice and snow, for the purpose of controlling his course. To see him coming head first down the leap is what the Scotch call uncanny. Hitherto, Mr Cornish has been particularly successful in negotiating the difficulties of the course, and had almost succeeded in obtaining converts to this way of tobogganing which at any rate has the charm of novelty. Unfortunately, however, he came to grief more than once during the race, though the extraordinary quickness of his recovery astonished the onlookers.

The Alpine Post consistently followed and reported on the activities associated with tobogganing and the races themselves with keen detail, commenting on toboggan design, personalities and techniques in these early days of the sport. For example, it included a detailed discussion of the importance of boots as a handicap. See Races and timekeeping. It also reported on accidents as tobogganers and pedestrians collided. For example:

It was here that on Tuesday last an unfortunate accident occurred to Mme La Barronne de Sinner. It appears that Mr G. Spence, who was descending the Run, came to grief at this corner, and in leaving the course his machine struck the lady with great violence...

The Film

The Cresta has been also filmed many times. Whilst it is to be expected that more and more amateur footage is appearing, and many of these can be accessed on the internet, The Cresta Run actually appears on film as early as 1925, and there are subsequent films of the Winter Olympics from both occasions. These can be accessed at The British Pathe Archive, which has recently been made available on You Tube. Link here

Not only is the development of the Cresta Run documented through the media, the descriptions of the run and the riders tell us as much about historical attitudes to amateur winter sports as they do about the Cresta itself. Here three early magazine articles are examined and other more modern articles can be accessed here.

James Bond went down a Cresta Run lookalike in “On Her Majesty's Secret Service”.

The Cresta Run is also shown in the documentation about Gunter Sachs' life.

Late 18th and early 19th centuries

There have been many articles published in the press and in popular magazines since 1885. Some naturally focus on the intricacies of such a unique sport, whilst others delight in the quirky 'Britishness' of the SMTC or the tradition of winter sports in Switzerland. There was flurry of interest in the The Cresta Run from the end of the 19th century and in the early 20th century. One of the earliest articles to be published, in 1895, entitled 'Tobogganing in the Engadine' appeared in The Strand Magazine, and was written by a woman - Celia Lovejoy. It begins;

When the enthusiastic tobogganer from the Engadine speaks on his return to England of his winter experiences as serious sport, his utterances are usually received with smiles of tolerant incredulity. This is because those English who are not personally acquainted with Alpine tobogganing seem to imagine it to be something after the style of the play that has lately been seen on the cliffs of Dover and the hills of Hampstead. This is a mistake.

-

1/4The Strand Magazine. “Tobagganing in the Engadine“ 1895 by Celia Lovejoy.

-

2/4The Strand Magazine. “Tobagganing in the Engadine“ 1895 by Celia Lovejoy: “The Cresta Run – Cresta Leap and Finish“

-

3/4The Strand Magazine. “Tobagganing in the Engadine“ 1895 by Celia Lovejoy.

-